Nietzsche, Suffering, and Hemingway

“Hills Like White Elephants” turns one couple’s pain into an engaging and beautiful literary puzzle for the reader to solve.

Friedrich Nietzsche’s life-affirming philosophy describes art as the great means of transfiguring human suffering. In the face of relentless, seemingly meaningless pain and humanity’s powerlessness to escape it, art generates beautiful illusions that make life bearable. Nietzsche contends that the truth of these illusions, or their capacity to faithfully imitate reality, is far from their highest purpose. He rejects truth as the “supreme value” and opposes humanity’s unconditional pursuit of knowledge, including science and Schopenhauer’s pessimism. [1] His philosophy stresses “untruth” as a condition of life — to endure the senseless cruelty of the world, one must seek refuge from knowledge. [2] Consequently, the great power of art lies in its ability to invent a “splendid illusion” that alchemically transmutes pain into pleasure. [3] More broadly, art serves as a model for transforming life’s pain and ugliness into something endurable. [4] Just as the spectator of a tragedy simultaneously believes the narrative before them and recognizes it as an illusion, one can practice knowingly lying to oneself as a means of living more beautifully.

With particular reverence for Greek tragedy, Nietzsche, a classical philologist, characterizes art as the product of dual impulses represented by the gods Apollo and Dionysus. The Dionysian impulse is chaotic, primordial, and emotional. In ecstatic frenzy, Nietzsche argues, one enters a Dionysian state and perceives the “terrible destructiveness of so-called world history as well as the cruelty of nature.” [5] This glimpse of reality paralyzes the one who gains knowledge, recalling Hamlet’s inability to take action. Conversely, the Apollonian impulse represents order, illusion, and logic, imposing a beautiful form over the chaos to save the “Dionysian man.” [6] Nietzsche argues that a balanced synthesis of the two is necessary to create great art. The Dionysian impulse supplies a truthful, emotional drive, while the Apollonian impulse invents formal beauty that ‘veils’ the terrible truth of existence, turning suffering into a source of pleasure.

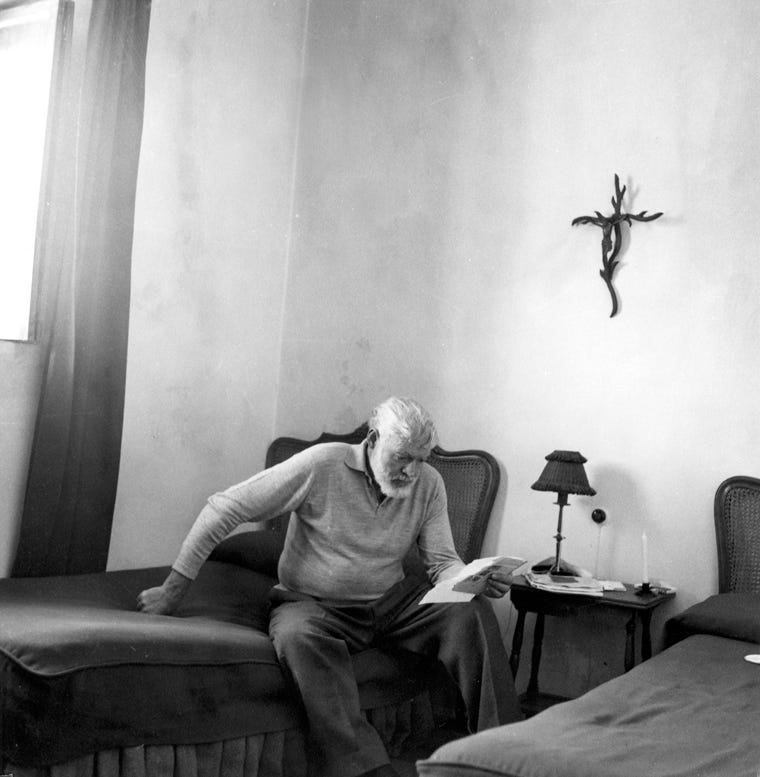

Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” brilliantly realizes Nietzsche’s vision of literature as the transfiguration of pain into beauty. The short story centers on a conversation between an American couple sitting at a bar beside a station in Spain as they await a train to Madrid. [7] In his characteristically terse prose style, Hemingway unspools a cryptic narrative, mostly through dialogue. The characters, referred to as “the man” and “the girl” (later called Jig), speak in vague statements and seemingly neutral observations while sipping beer. “They look like white elephants,” the girl remarks early on, referring to the hills across the valley (p. 273). The dialogue shifts from commentary on their surroundings to the man pressuring Jig to undergo an “operation.” Jig expresses ambivalence and questions whether their relationship will revert to its previous happiness if she agrees. The man persists and Jig finally asks him to stop talking. The man observes other travelers waiting for the approaching train and returns to the table, where Jig repeats twice that she feels “fine,” concluding the story (p. 278).

Despite its seemingly trivial nature — or, more significantly, because of it — Hemingway’s dialogue carries unspoken emotional depth. As the reader gradually realizes, the couple is indirectly discussing Jig’s pregnancy, the prospect of an abortion, and their future together. The story finds the pair caught in a state of terrible suffering. The pregnancy has thrown their lives into disorder and colored the relationship with miscommunication, uncertainty, and fear at a time when abortion is legally and socially taboo. It is the chaotic and unbearable Dionysian truth that gives the story emotional weight. The story’s formal features embody its redemptive Apollonian impulse, turning the couple’s pain into an engaging and beautiful literary puzzle for the reader to solve. Namely, Hemingway withholds significant information about the couple and their situation, including their history and Jig’s pregnancy. The story begins in medias res and ends on an ambiguous note. To build on the intended effect, Hemingway adopts an unobtrusive narratorial stance. He also relies heavily on parataxis in his sentence structure; the story’s restrained prose refuses to elucidate or comment on the events it portrays, leaving much for the reader to determine independently.

In this way, “Hills Like White Elephants” turns the reader into a detective, prompting one to make guesses, continually revise them as the story goes on, or reread. Its formal elements transfigure the couple’s miscommunication and tragic circumstances into a beguiling riddle whose solution satisfies us. In the Nietzschean sense, the story models the handling of “white elephants” — burdensome conflicts and social taboos, especially those rooted in gender — by approaching them as engaging puzzles. This constitutes the story’s ultimate value and moral justification. Solving a puzzle requires ingenuity, vision, and curiosity. Reading “Hills Like White Elephants” teaches the reader how to confront the unspeakable challenges of life in a similarly imaginative way, fostering a less shameful and more harmonious existence.

First, Hemingway withholds significant information, implying some details and omitting many outright. These gaps engage the reader in a rewarding effort to make sense of the narrative through careful investigation. The story introduces its central characters simply as “the American and the girl” (p. 273), passing over age, physical description, and other traits. Only the man’s nationality is specified. Although the opening description states that “the express from Barcelona would come in forty minutes” (p. 273), Hemingway never elaborates on the couple’s origin or reason for traveling to Madrid. The reader immediately becomes curious about their identity and circumstances, attracted by the unknown. Above all, the story subtly implies Jig’s pregnancy and the potential abortion without explicitly informing the reader. Her comparison of the hills to white elephants, for example, gains significance as the story goes on. Far from a throwaway observation, the image of a “white elephant” — a precious but ultimately inconvenient gift — evokes child-rearing (p. 273). The reader looks to this subtle detail as a clue for making sense of the story. Hemingway offers sufficient information to stimulate the reader’s deductive reasoning but conceals the basic facts. For example, the characters refer to the abortion as an “operation” or, repeatedly, “it” (p. 275). Their vague language establishes the central mystery of the text for the reader. From the man’s first mention of an “operation,” the reader becomes captivated by the unknown and the pursuit of understanding. The disorder and fear underlying the couple’s miscommunication serve as the Dionysian impulse that creates emotional vitality. Simultaneously, the Apollonian device of omission turns the painful situation into an alluring puzzle, generating the cognitive pleasures of speculation and decryption.

Hemingway’s manipulation of time produces a similar effect as his withholding of information. The story begins in medias res, without preamble or a lengthy build-up to the action. In the second sentence, Hemingway writes, “On this side there was no shade and no trees” (p. 273). The immediacy of the clause “on this side” plunges the reader into the scene, creating a sense of disorientation. The very setting of a train station — a place of transience and movement between two fixed points — also contributes to the feeling of stepping into the middle of a narrative. The dialogue begins abruptly, as if preceded by a conversation that took place off the page before the story’s opening paragraph (p. 273). Hemingway suggests the characters share a deep history, contributing to the mystery that fascinates us. For the remainder of the story, the reader witnesses every moment of the couple’s conversation. The story’s continuous attention to the dialogue signals its importance, despite the obscurity of their statements. This tension creates additional interest for the reader. To conclude, the seemingly arbitrary moment that ends the story leaves a host of questions unanswered. Jig sits at the table and smiles at the man. “‘I feel fine,’ she said. ‘There’s nothing wrong with me. I feel fine’” (p. 278). Her statement and its implications for the couple’s future remain ambiguous. Jig saying she “feels fine” could suggest an acceptance of the man’s wishes and her decision to receive an abortion. Alternatively, it could be an assertion that she sees “nothing wrong” with her pregnancy and will refuse an abortion. This uncertain ending completes Hemingway’s elegant puzzle. Although some may find it unsatisfying, the final note of ambiguity ensures the mystery will reverberate in one’s mind after finishing the story. From beginning to end, Hemingway’s control of time adds to the reader’s curiosity, turning the couple’s struggle into a source of fascination.

Next, Hemingway’s narration refrains from explanation of the story, leaving the reader to work out its significance. The narrator is a nearly invisible presence. Without a personality or any impact on the events, he relates the story simply, never judging the characters’ actions or introducing an external perspective. The story’s lack of adverbs and adjectives reflects this attitude. In particular, the narrator provides little information regarding the characters’ tone, expression, or actions during each line of dialogue. An early exchange concerning absinthe, when the man tells Jig to “cut it out” and she responds that she was “being amused” (p. 274), demonstrates such ambiguity. In the absence of adverbs or further description, the reader could interpret the dialogue as hostile, sorrowful, flirtatious, or meaningless. The couple’s statements and questions throughout the conversation are similarly unadorned, inviting attempts to understand the characters’ motivations. More broadly, the story’s reliance on dialogue over description allows Jig and the man to speak for themselves without obtrusion. In this way, the narratorial stance aims for minimalism as a means of heightening the mystery and the reader’s fascination.

The story’s sentence structure enhances this effect. Hemingway uses parataxis — the simple arrangement of clauses alongside each other — to avoid weighing elements unequally or relating events to one another. This style flouts hierarchy and makes the reader more active in parsing the relevant data. For example, the following sentence comes during a break in the conversation: “They sat down at the table and the girl looked across at the hills on the dry side of the valley and the man looked at her and at the table” (p. 277). No punctuation or linguistic variation elevates one clause above another. Nor does the sentence explain the relationship between the couple sitting at the table and their contrasting gazes. Instead, Hemingway’s repeated use of “and” produces an uninterrupted flow of information for the reader to interpret. One could understand this moment as the product of shame, tension, peace, or another emotion. Whatever the interpretation, parataxis has the effect of drawing the reader into a puzzle-solving frame of mind. As a formal feature, it makes for a significantly more captivating artwork than a conventional narrative relaying the couple’s challenges.

In summary, a close reading of “Hills Like White Elephants” as an illustration of Nietzsche’s theory reveals a superb transfiguration of suffering into beauty. Through an array of formal features, the story crafts a captivating puzzle, rendering the couple’s unspoken pain, uncertainty, and miscommunication a source of cognitive pleasure. The withholding of information makes the reader an engaged participant who must do work to appreciate the text. Some may object that the transfiguration of real-world issues — gender inequality, reproductive autonomy, and anxiety around pregnancy — into a form of enjoyment is immoral. Yet, the story’s Apollonian impulse teaches the reader a method of facing shameful conflicts in their own life, leading to the potentially more significant outcome of harmony and freedom. Legal restrictions and cultural taboos surrounding gender remain especially relevant to modern readers. Just as the couple must avoid speaking frankly in public, we may frequently encounter similar failures of communication. Perhaps Nietzsche would instruct readers to learn from Jig’s imaginative comparison of the hills to white elephants as a microcosm of Hemingway's form. With the transfiguration of a taboo into an alluring puzzle, replete with clues and hidden facts, the story demonstrates how to regard one’s own challenges with active fascination and vision.

Endnotes

[1] Friedrich Nietzsche, "Art in the 'Birth of Tragedy,'" trans. Walter Kaufmann, in The Will to Power (New York: Vintage Books, 1967), 853 [3]. [2] Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, trans. Helen Zimmern (Leipzig: C. G. Naumann, 1886), 4. [3] Friedrich Nietzsche, "The Birth of Tragedy, Or: Hellenism and Pessimism," trans. Walter Kaufmann, in Basic Writings of Nietzsche (New York: Modern Library, 1992), 143. [4] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Vintage Books, 1974), 107. [5] Nietzsche, "The Birth of Tragedy" 59. [6] Nietzsche, "The Birth of Tragedy" 60. [7] Ernest Hemingway, "Hills Like White Elephants," in The Short Stories (New York: Scribner, 2003), 273-78.