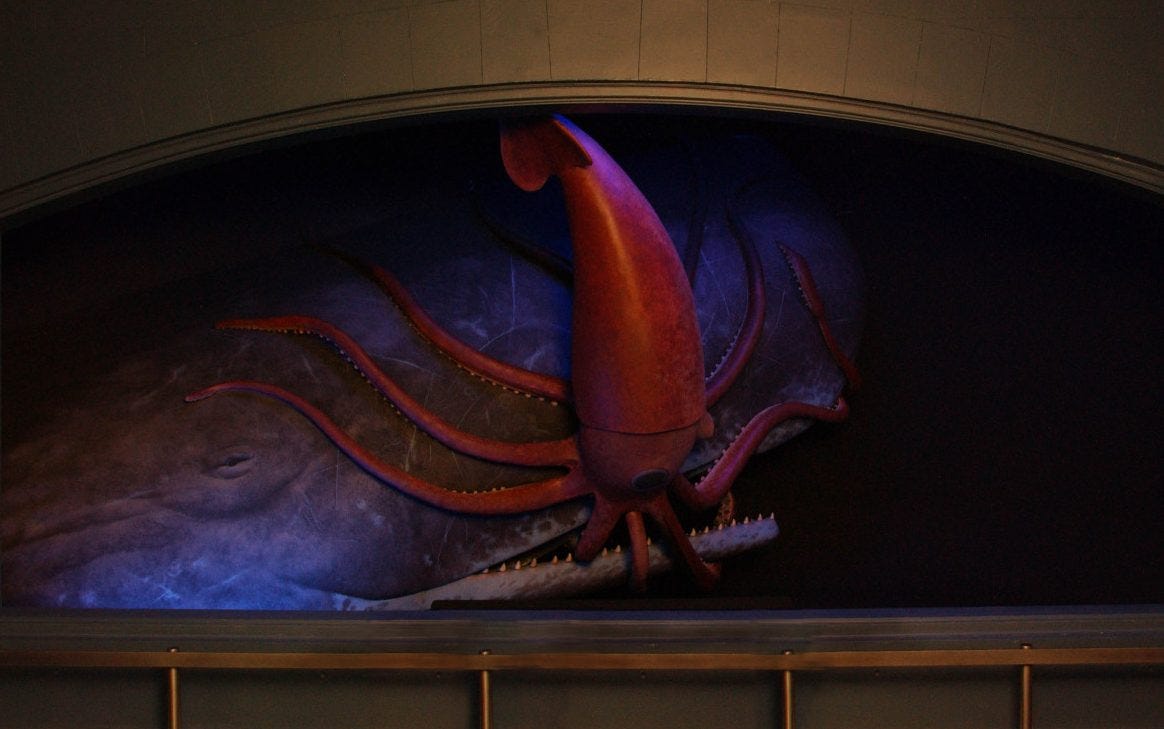

The Squid and the Whale

Upon leaving the theater, I understood my eight-year-old self to be impossibly insignificant, a side effect that usually persisted for several hours.

In those days, we made a pilgrimage across Central Park nearly every month, always on a Sunday. My father, still able to read without his glasses, dutifully guided us over the Great Lawn and toward our destination—the American Museum of Natural History. As budding agnostics, it was the closest thing my sister and I had to a regular place of worship. “Journey to the Stars,” a show at the planetarium narrated by Whoopi Goldberg, was my weekly sermon. On every visit to the museum, I begged my dad to spend an extra ten dollars so I could see the show for a second, fourth, eighth time. He always said yes.

One afternoon, the three of us boarded the elevator that brought us to the space auditorium, 50 feet in the air. Entering the vast rotunda, I chose my soft velvet chair, aiming to see as much of the screen as possible. Unlike in an ordinary theater, the planetarium show projected images onto a domed ceiling, so audience members had to crane their heads to see the cosmic events unfolding above them. The idea, I assume, was to simulate the experience of the night sky. More often than not, my sister, father, and I left the theater with a crick in our necks. I didn’t mind. On that afternoon, as the lights dimmed, I gazed up at the kaleidoscopic dome above me and felt sheer awe. “Thirteen billion years ago, the very first stars were born,” Whoopi intoned. As she spoke, swirling nebulae collided and collapsed, erupting into a thousand points of colored light. Galaxies were ruptured, planets born. Time seemed not to exist during “Journey to the Stars”—whether the show’s runtime was ten minutes or two hours, I cannot say. What stands out in my memory is the mix of terror and reverence that gripped me on afternoons spent at the planetarium. I do not exaggerate when I describe our visits in religious terms. Upon leaving the theater, I understood my eight-year-old self to be impossibly insignificant, a side effect that usually persisted for several hours. And still I returned, month after month.

I found another sanctuary in the Hall of Ocean Life. To get there required navigating the hall of biodiversity, which featured a life-size dodo bird sculpture and a lush rainforest model. Eventually, the green of feigned African tulip trees gave way to a rippling blue light, signaling that we were crossing over to another world. Descending two flights of stairs brought us to the main level, where diorama sculptures of marine animals lined the walls. Behind one glass pane was a vaguely depressed manatee, suspended in midair. At another window, a pod of dolphins competed for the same fish. My favorite of them all depicted a sperm whale and a giant squid locked in vicious combat, 6500 feet under the sea. It was an epic battle, fought entirely in darkness. Even as the whale snatched his opponent in his jaw, the squid struggled relentlessly to break free, splaying her tentacles against the whale’s pained face. Something about the darkness of the scene attracted me. Even more intriguing was the obscurity of the two species; the first confirmed recording of a giant squid in the wild was as recent as 2005. The diorama naturally became my favorite corner of the entire museum. My father and sister both understood, in the way family members do, that the squid and the whale belonged to me. On certain occasions, they left me alone there for long stretches of time. I was content to stand before my sea monsters, imagining myself at the ocean floor. Besides, I had another guardian watching over me: a 94-foot blue whale hung from the ceiling, surveying her human visitors below. Next came a cafeteria meal of dinosaur-shaped chicken nuggets, grape juice, and black-and-white cookies.

I have not returned to the museum for several years now, barring the occasional class trip to the Hall of Evolution. Since those summer weekends, I imagine other children have claimed my diorama as their own. Renovations will have desecrated the exhibits that my sister and I loved so well. The planetarium, which appeared colossal in my childhood eyes, might seem cramped, even run-down. And without her at my side, visiting the museum would seem like a betrayal. One day, though, I predict the three of us—my sister, father, and I—will retrace our steps. We will walk the same Central Park paths, crane our necks to the dome, peer at aging dioramas. We will try to see the world as we did in younger days, and we will fail.